Tasks Versus Skills Part 1: Squaring the Circle of Work with AI

A 7-part series and on AI, the state of tasks versus skills, and some provocative what-if concepts for Learning and Development, HR and Talent teams.

This is Part 1 of a series called Tasks Versus Skills: Part 1: Introduction, Part 2: Playbook, Part 3: Let Learning Breathe, Part 4: Task Intelligence Control Room, Part 5: Tasks as EX Product, Part 6: IQA Prototype, Part 7: Talent Is Not a Commodity; Google Books “Tasks vs Skills” free ebook (Parts 1-6 only).

The idiom ‘square the circle’ refers to solving an extremely difficult problem, perhaps trying to reconcile different ideas, conditions, or perspectives. It means constructing a square with the same area as a circle with a compass and straightedge or ruler. Historically, squaring the circle was considered an impossibility for mathematicians and philosophers. Futile. Considering a more optimistic idiom, however, a rare ‘once in a blue moon’ opportunity appears to be upon us today, particularly for those in corporate Learning & Development (L&D) engaged in skills-first strategies.

The world of work is changing rapidly, and the skills we need to succeed are evolving faster than ever before. While a strong focus on skills development is crucial, many organizations find that a sole skills-based approach is insufficient. There's a missing piece of the puzzle: tasks. Tasks are the building blocks of work, and understanding how they connect with skills is essential for developing effective workforce strategies, particularly as AI becomes increasingly integrated into our workflows.

Yet, I see a dilemma.

Proportional value

For the past few years, employee development has seen a significant rise or focus unique to skills, skilling, and modernizing companies into a Skills-Based Organization, or SBO. The goal is to advance new methods to identify gaps in knowledge and ability, new approaches to fill skills gaps and sustain at-scale programs to ensure gaps are addressed with some level of predictability.

There is, however, a proportional dilemma. Developing skills is certainly a non-negotiable. This is mandatory to stay competitive and healthy and protect or future-proof individuals and enterprises. The dilemma regards an internal over-reliance on a skills-first mindset as a somewhat dominant charter. This is often fueled by external vendor influence, industry analysts, and, in some cases, propaganda or fear not to miss the skills boat.

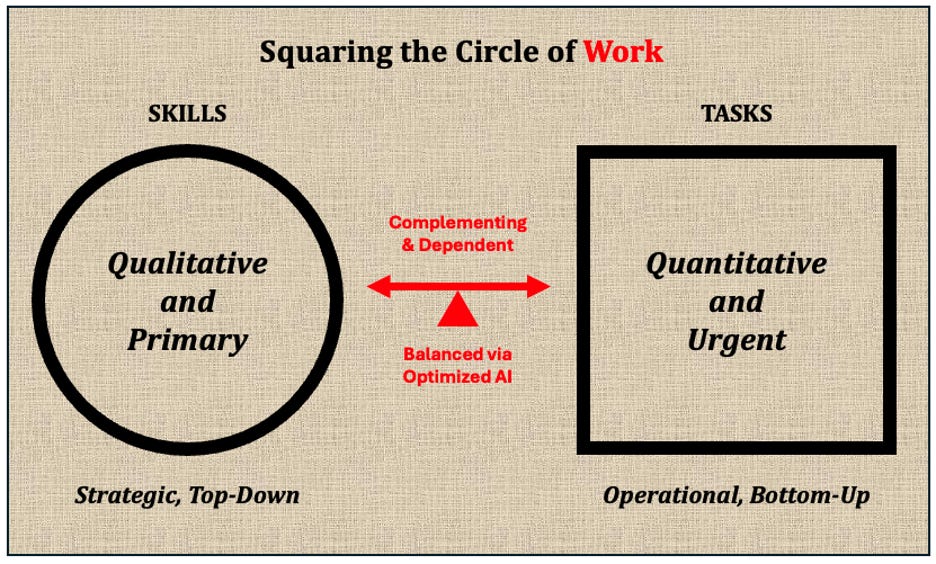

What’s missing is acknowledging the proportional value of tasks, quantifiable tasks with the complementary value of skills, qualified skills.

A task is a specific work assigned to be completed within a certain timeframe. It often requires various skills to be executed successfully.

Skills are divided into basic skills (like active listening or reading comprehension) and cross-functional skills (e.g., critical thinking, time management). They enable workers to perform tasks effectively.

Given the heightened focus and fascination for skills-centricity, tasks appear to have been downplayed or deprioritized in favor of progressing SBO agendas. Skills are, again, absolutely critical. This write-up aims to re-establish or elevate the importance of tasks versus skills, share some challenges with SBO approaches, and showcase artificial intelligence’s stronger alliance with tasks first and skills second. We’ll also share some pro-tasks arguments, and end with some provocation; that is, four ‘what-ifs’ to harmonize my thesis below.

First, let’s consider a real example to better frame this skills versus tasks topic. A customer service department is experiencing low customer call resolution rates and decreasing customer satisfaction. The call center’s management assumes that improving customer service requires developing new skills in agents through extensive training programs on communication, product knowledge, etc. [1]

However, via more quantitative research that broke down customer interactions into specific, measurable tasks, the findings revealed the real issues:

Inefficient call routing led to long wait times and eroding customer satisfaction

Lack of call center workers’ access to relevant information during support calls, resulted in customers being on hold too many times

Repetitive tasks take up agents' time, preventing them from focusing on higher-value activities

The results of implementing targeted AI assistance:

Access to task-specific AI assistance increased productivity by 14% on average

For novice workers, productivity improved by 34% by isolating inefficient tasks

Related, task-based support from AI support enabled newer call center agents (2 months tenure) to perform at the same level as experienced agents (6+ months tenure)

More specific to a customer service role, is the ability to increase one’s level of Empathy with customers given AI’s time- and effort-savings

My thesis

With this framing in mind, here are my eight beliefs justifying a proportional value of tasks in a current disproportionate domain of skills and SBOs:

Task-level focus defines and measures work more accurately: Work is most precisely defined, conducted, and accomplished at the task level. This approach optimizes real problem-solving by focusing on tangible outcomes and enabling immediate impact and feedback.

A task-centric approach optimizes problem-solving and impact: Tasks focus on specific outcomes, enabling immediate impact, removing ambiguity, and capturing complexity in a directly measurable way.

Task execution trumps theoretical and abstract skill attainment: The successful execution of a task is more valuable than the attainment of a skill not applied, i.e., what you know does not always correlate with what you can do well.

Tasks provide concrete evidence of capabilities: The most efficient way to demonstrate skill attainment and portability across job roles is through specific work activities and accomplishments. Task measurement offers a more objective and clear assessment of performance.

Performance is best judged through task measurement: Tasks are binary— completed correctly or not—making performance easier to measure objectively compared to skills requiring assessing potential or capability.

Balancing tasks With skills improves your skills strategy: Current skills-based strategies and SBOs often face implementation challenges due to unrealistic expectations and lack of a balanced approach. A proportional focus on skills and tasks can lead to more effective organizational development. That is, a skills strategy will best succeed via complementary skill-enabling tasks.

AI optimization aligns better with task-centric approaches: Generative AI, Large Language Models (LLMs), and other advanced technologies, including Agentic AI, excel in optimizing task-level efficiencies and productivity and ensuring systems can operate effectively. This technology-driven approach differentiates tasks from more abstract skill concepts, making AI-driven optimization more feasible and effective.

Tasks organically evolve across multiple dimensions: Skills tend to be contained in firm, static catalogues or in a single taxonomy and ontology dimension. Specific units of work, or tasks, have an ‘organic latitude’ that bridges several domains including across multiple work dimensions (industry, business function, mission and values, etc.).

This thesis aims to clarify and justify a more balanced and reciprocal value via tasks. This is not to devalue the crucial need for strategic skill development. Rather, I hope to reinvigorate a more realistic and pragmatic understanding.

Squaring the circle of today’s work is possible if we understand the differences, dependencies, and proportional value of skills and tasks. This includes complementing qualitative skills typically enabled by a top-down or at-scale mandate, with a balance of quantitative tasks often enabled via a bottoms-up, urgent, operational practicality and optimized AI.

Is the juice worth the squeeze with a Skills-Based Organization approach?

Skills-based organizations have been promoted as the future of workforce development, promising agility, mobility and the ‘democratization’ of talent. However, recent experiences and analyses indicate that SBOs do not consistently meet expectations in practice. Why are SBOs falling short? Are we trying to boil the ocean? The answer lies in a possible overzealous focus on skills at, perhaps, the expense of tasks. While skills are undoubtedly important, they are an equal half of the equation.

Here are some findings on why SBOs may be struggling to deliver.

Overly complex skills taxonomies and wrangling fractured skills data. Many organizations attempt to build extensive, hierarchical skills taxonomies and supporting systems, but these often prove unwieldy and lack practical application. The complexity arises because industries, companies, and job roles require different interpretations of skill sets, making it difficult to create coherent and actionable skill maps. While skills taxonomies aim to provide a structured framework for categorizing organizational skills into groups and proficiency levels—helping HR teams identify, assess, and manage skills effectively—their implementation frequently leads to endless debates and delays. Kaisa Savola highlights in “Challenges Preventing Organizations from Adopting a Skills-Based Model” that “Developing a company-specific skills taxonomy is a complex task that requires a deep understanding of current and future skills needs... This overwhelming complexity can lead some companies to delay or abandon the effort.”

The challenge is further exacerbated by the need to collect and categorize skills data efficiently. Whether stored in spreadsheets, SharePoint sites, or massive data lakes, tagging skills accurately—by name, category, proficiency level, and other metadata—requires significant effort and coordination. Years of untagged learning content, poor governance, and inconsistent definitions often force organizations into time-consuming and expensive efforts to address these gaps, ultimately impeding the effectiveness of skills taxonomies.

SBOs don’t always address specific business problems, and gaining support remains an uphill battle. Instead of focusing on skills in isolation, companies need to start by solving real-world problems. Josh Bersin notes that too many organizations start with broad skills frameworks without connecting them to actual job performance or outcomes. Bersin’s colleague Deoné Duffy adds: “Many organizations rush into skills-based systems without aligning them to business outcomes, which leads to wasted efforts and resources. Identifying specific challenges should be the first step".

Even if there is alignment, skill-building remains a low priority. As shared in a BCG study of 120 large global companies: [2]

“Despite the clear importance of skill building and the significant budgets devoted to it, most leaders view it simply as an expense, not unlike equipment maintenance… As the chief human resources officer of a global industrial goods firm told us, “When there is pressure on costs, the first thing to be cut is the learning and development budget. How do we expect the business to sustain results when the core resources—the people—don’t have the capabilities to deliver?”

Failure to Adapt to Changing Needs. Another issue with a skills-centric approach is that many organizations struggle to update their skills catalogs to match evolving business needs. For example, the shelf life or application of some IT skills from just 5 years ago may no longer be relevant today. A lack of flexible durability. This failure to adapt skills models in line with changing business and technological needs can lead to a misalignment between employee capabilities, development planning with one’s manager, and accurate goal setting.

“The executives estimate that nearly half (49%) of the skills in their workforce today won’t be relevant in 2025. The same number, 47%, believe their workforces are unprepared for the future workplace. Identifying skills shortages is not a surprising result to come out of an educational platform provider, but the short timespan is an eye-opener.” [2]

Limited impact on real, measured performance: One of the most significant criticisms of SBO intentions is that focusing on skills in isolation does not always translate to better performance. To enable competence at-scale, especially with multi-national companies, skills assessments often remain generic, lacking specificity, and don’t always measure an employee’s ability to complete tasks effectively. As HR analytics leader Nicolas Behbahani points out: "The overemphasis on skills often leaves organizations with a false sense of progress. It's the ability to apply those skills in real-world tasks that matters".

Meanwhile, only 4% of companies report on the outcomes of their skill-building programs regarding business outcomes (such as improved productivity or application of a new tool at work) or talent outcomes (such as higher employee engagement or participants' employability). [3]

A mismatch with skills, roles and expectations. Even with a well-constructed skills framework, there’s often a mismatch between the identified skills and the roles employees are expected to perform. For example, American Express discovered that their customer service teams didn’t need traditional service skills, but rather hospitality skills: “The ‘skills’ needed in the Amex sales and service teams were not customer service skills at all, but hospitality skills... It took a skills-based analysis to figure this out.”

Additionally, from Felipe Hessel, Global Skills & Strategic Workforce Planning Director at Sandoz, "Tasks have a strong connection to roles. Roles ring fence or can confirm what a role should be doing at that task level, and therefore what good performance should look like. It's a value chain. Skills are what result from the tasks being executed well. I believe this connection is important as roles and tasks are more tangible for the business compared to a singular focus on skills.

Udemy Business’ recent report "Workplace 2.0: The Promise of the Skills-Based Organization" shares the same SBO sentiment and expands on several key themes: [4]

Awareness and familiarity: There's a significant gap in understanding SBO concepts based on job roles, with managers and above being more familiar (45%) compared to individual contributors (30%) and job seekers (20%).

Challenges and barriers: 70% of respondents report observing challenges or barriers to adopting skills-based practices.

Leadership’s role: While 83% of senior leaders identify effective leadership as critical to the SBO transition, only 28% of respondents feel their leadership team is communicating the company's SBO strategy and initiatives well.

Expanding on leadership role challenges during a leader’s SBO deployment: “Only 29% of all respondents report that their leadership team is very or extremely well equipped to address these important considerations.” Udemy’s report adds: “Leaders who are attentive to the nuances in how employees view the transition to skills-based practices will be better positioned to understand areas that are working well and others that need more attention. This data can provide leaders with better tools to lead an effective and inclusive transition.”

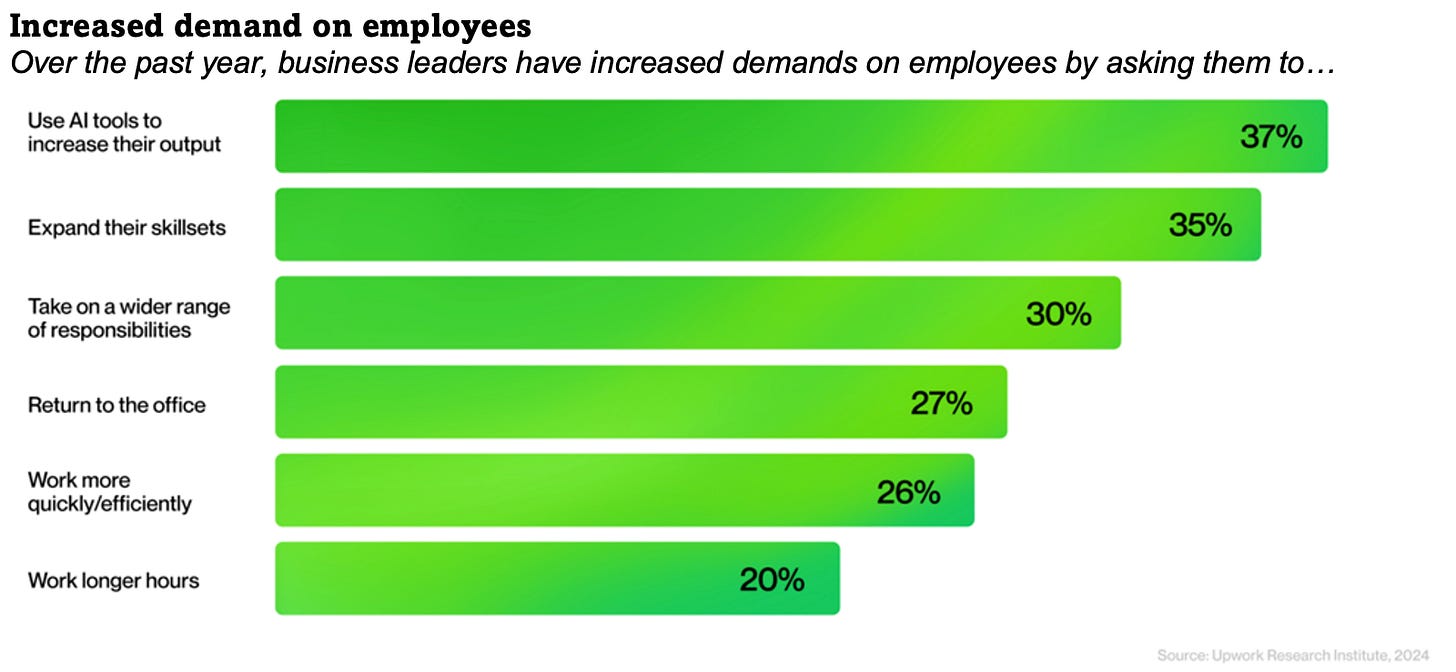

There also appears to be a disconnect of expectations that may impact a SBO’s success. In Slack’s Fall 2024 Workforce Index report of over 17,000 desk workers, executives remain excited about AI at work with 99% planning to invest. Desk workers are similarly excited to upskill with 76% sharing an urgency to build GenAI expertise. Yet, when considering the daily realities of today’s work, what executives and management perceive as benefits of AI, employees share hesitations, specifically towards AI tools actually increasing their workload.

“Employees are worried that the time they save with AI will actually increase their workload — with leaders expecting them to do more work, at a faster pace,” shares said Christina Janzer, head of the Slack Workforce Lab. “This presents an opportunity for leaders to redefine what they mean by ‘productivity,’ inspiring employees to improve the quality of their work, not just the quantity.”

Additionally, many employees share reluctance about their use of AI in daily work. Janzer adds: “Our research shows that even if AI helped you complete a task more quickly and efficiently, plenty of people wouldn’t want their bosses to know they used it”. For those surveyed who shared hesitations about informing their manager about using GenAI, three reasons rose to the top:

Feeling like using AI is cheating (47%)

Fear of being seen as less competent (46%)

Fear of being seen as lazy (46%)

The Workforce Index report also highlights a disconnect between management’s expectations of AI’s benefits (i.e., more learning, more innovative projects to work on...) compared with employees’ views of more administrative work, despite really wanting less work activities on their plate.

The impact to SBOs is two-fold. First, there is resounding support that in this new age of AI, learning new skills is a shared top priority. This is great. Regardless, the potential misalignment of intentions and expectations between executives and employees may be a concern to assess and monitor.

Concluding with two key, sensitive, SBO challenges from Udemy’s report:

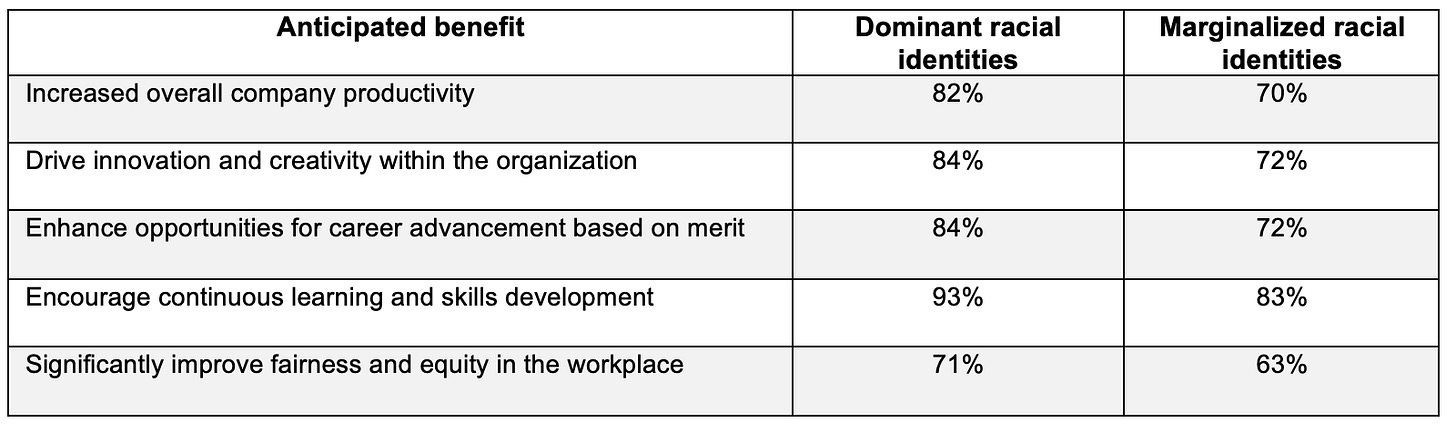

Equity and Inclusion: While SBOs have the potential to break down barriers for historically underrepresented groups, only 18% of employees have observed improvements in fairness and equity in the workplace due to skills-based initiatives. This demonstrates a disconnect between the promise of a more inclusive workforce and the actual outcomes observed so far. “It is clear that most people do not yet believe that an SBO has the potential to improve equitable opportunities in the workplace. This perspective is even more apparent when we compare the reactions of dominant groups to historically marginalized racial groups. Dominant groups anticipate more overall positive impacts than their colleagues belonging to historically marginalized groups...” (See Appendix A)

Employee Sentiment: The report also shows mixed feelings about SBOs among employees. While a majority are excited about the potential of SBOs, others express uncertainty, anxiety, and confusion, especially younger workers and those from historically marginalized groups. This highlights the need for organizations to better communicate the benefits and address concerns to ensure buy-in from all employee groups.

“A skills-based strategy has the potential to lead to a workplace that is more inclusive of and accessible to employees of diverse backgrounds. However, equitable practices need to be evident to employees in order to sway their opinions... Employee sentiment is an indicator of where invisible accelerators or barriers exist that can either facilitate progress and outcomes or impede momentum and detract from the potential benefits of SBO.” [4]

AI’s unsung, grassroots hero: Tasks

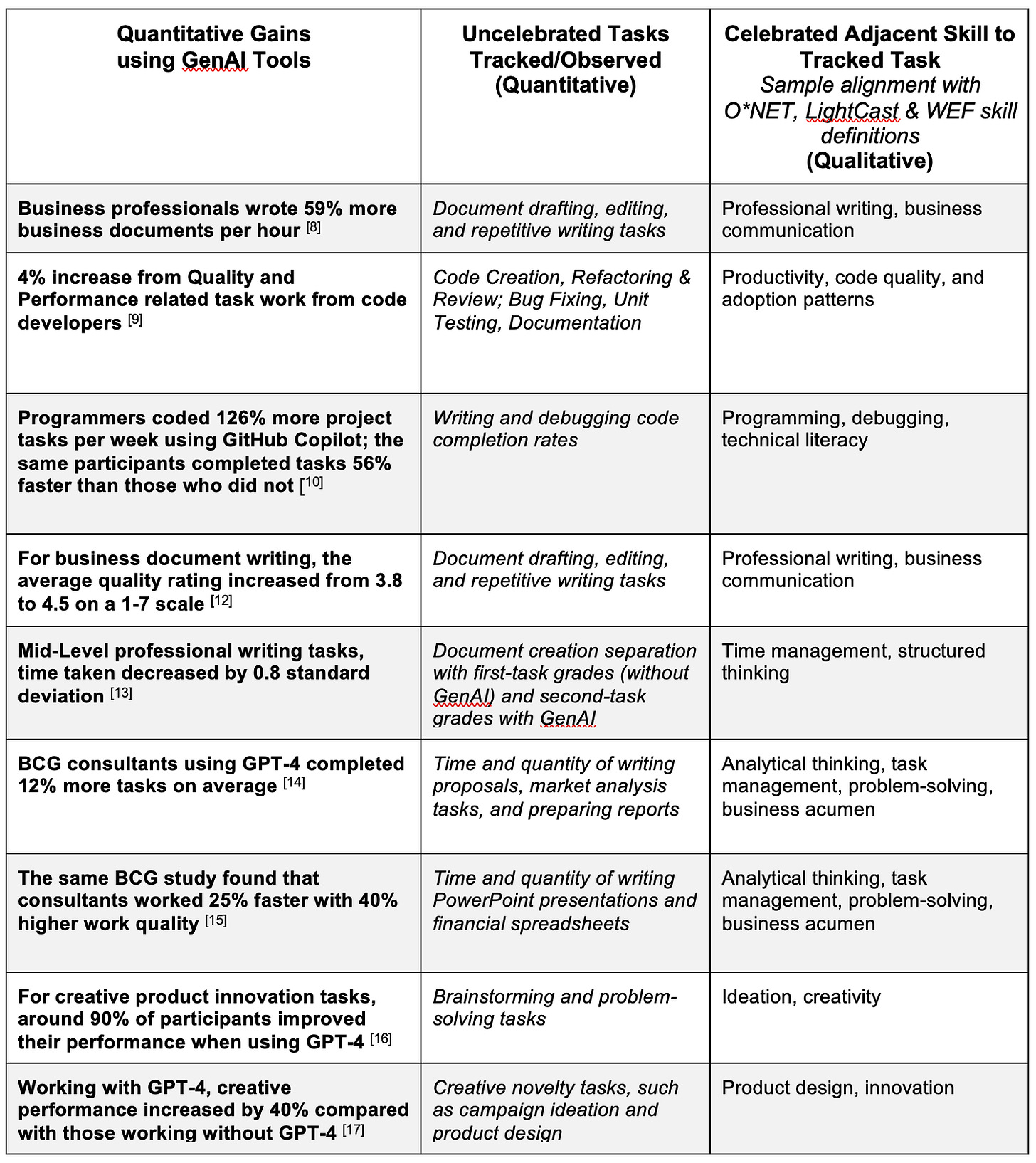

It seems that recent reports of efficiency gains and cost-savings from the use of Generative AI approaches are in volume. When exploring what was actually measured, in many cases, the evidence lies with the tasks that are being tracked and executed versus the skills expected and taught. GenAI tools like ChatGPT excel at the task level because they are inherently designed to work with specific, measurable outputs. This includes well-defined processes with clear goals, such as outlining draft concepts, basic coding, or responding to customer support needs or ticket types.

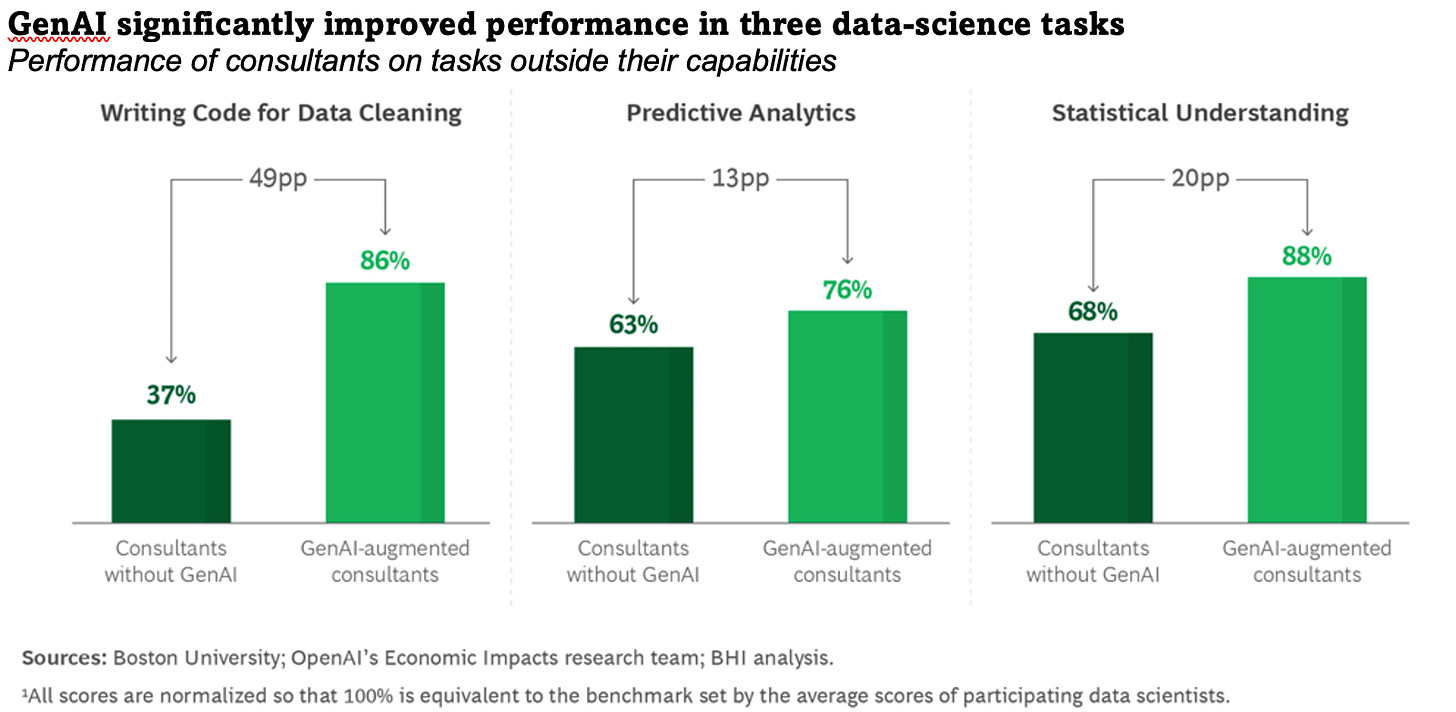

AI excels at optimizing task performance in real-time due to its alignment with measurable, discrete objectives, such as call resolution times or customer satisfaction rates. An example is BCG’s recent study on consultants who were building new data science capabilities focused on these 3 task areas below. Even without prior experience, consultants equipped with generative AI tools successfully wrote code, applied machine learning models effectively and identified and corrected errors in statistical processes. [5]

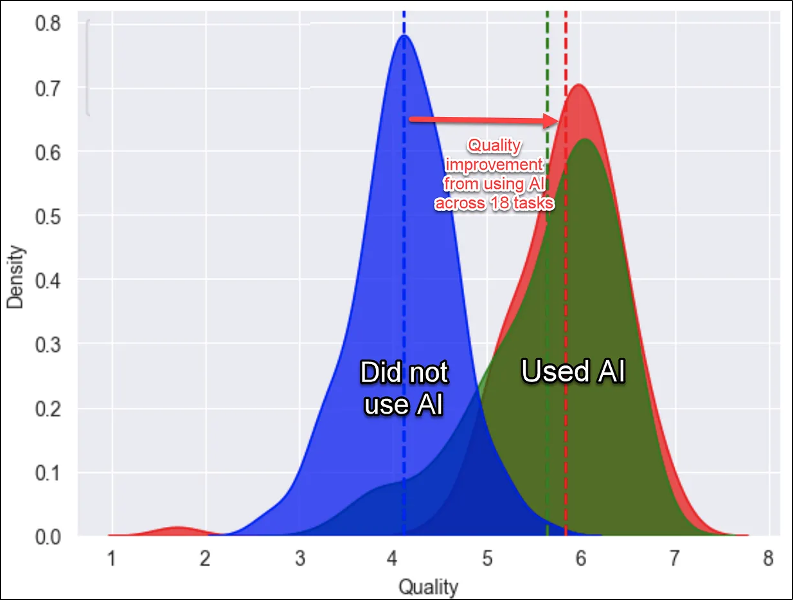

Similarly, as identified by the research paper “Navigating the Jagged Technological Frontier: Field Experimental Evidence of the Effects of AI on Knowledge Worker Productivity and Quality”, there is a notable improvement in the quality of production, productivity and task outputs when leveraging AI tools. [6]

However, to be fair, improved productivity does not mean workers are improving their engagement or happiness. Rather, burnout appears to be increasing despite meeting leadership’s expectations. (See Appendix B)

As reported from The Upwork Research Institute’s July research: “Now, leaders are eager to channel this enthusiasm… [However], employees are feeling the strain. Seventy-one percent are burned out and nearly two-thirds (65%) report struggling with increasing employer demands. Burnout is high across generations and genders: 83% of Gen Zers are burned out, compared with 73% of Millennials, 71% of Gen Xers, and 58% of Baby Boomers. Women (74%) report feeling more burned out than men (68%). Alarmingly, 1 in 3 employees say they will likely quit their jobs in the next six months because they are burned out or overworked.” [18]

While there appears to be progress, innovation and productivity gains with a task-centric approach, we are still in a very nascent state. And the speed of AI impacting both tasks and skills is leading to some debate, or at a minimum, increased ambiguity of where to play, and sorting the what’s-in-it-for-me next steps.

In Part 2, Seven playbook takeaways on how to win with AI, tasks, and skills, we’ll discuss some alternative approaches to address these questions.Despite a league of growing tension, the abundance of probable skepticism remains, I think, very healthy and motivating.

Links: Part 1: Introduction, Part 2: Playbook, Part 3: Let Learning Breathe, Part 4: Task Intelligence Control Room, Part 5: Tasks as EX Product, Part 6: IQA Prototype, Part 7: Talent Is Not a Commodity; Google Books “Tasks vs Skills” free ebook (Parts 1-6 only).

Special thanks to colleagues who guided me as contributors and reviewers, and to so many who have inspired my thinking and curiosity on this subject.

Contributors: Cathy Moore, Clark Quinn, Felipe Hessel, Gianni Giacomelli, Giri Coneti, Jon Fletcher, Julie Dirksen, Megan Torrance, Nick Shackleton-Jones, Nina Bressler, Will Thalheimer, Ross Dawson

Inspirations: Allie K. Miller, Amanda Nolen, Andrew Kable (MAHRI), Bhaskar Deka, Brandon Carson, Brian Murphy, Chara Balasubrmanian, Dani Johnson, Darren Galvin, Dave Buglass Chartered FCIPD, MBA, Dave Ulrich, David Green 🇺🇦, David Wilson, Deborah Quazzo, Dennis Yang, Detlef Hold, Donald Clark, Donald H Taylor, Dr Markus Bernhardt, Dushyant Pandey, Egle Vinauskaite, Emma Mercer (Assoc CIPD, MLPI), Ethan Mollick, Gordon Trujillo, Guy Dickinson, Harish Pillay, Hitesh Dholakia, Isabelle Bichler-Eliasaf, Isabelle Hau, Joel Hellermark, Joel Podolny, Johann Laville, Jon Lexa, Josh Bersin, Josh Cavalier, Joshua Wöhle, Julian Stodd, Karen Clay, Karie Willyerd, Kate Graham, Kathi Enderes, Marga Biller, Marc Zao-Sanders, Meredith Wellard, Mikaël Wornoo🐺, Nico Orie, Noah G. Rabinowitz, Nuno Gonçalves, Oliver Hauser, Orsolya Hein, Patrick Hull, Peter Meerman, Peter Sheppard, Dr Philippa Hardman, Raffaella Sadun, Ravin Jesuthasan, CFA, FRSA, René Gessenich, Ross Dawson, Ross Garner, Sandra Loughlin, PhD, Simon Brown, Stacia Sherman Garr, Stefaan van Hooydonk, Stella Collins, Trish Uhl, PMP 👋🏻, Tony Seale, Zara Zaman

Acknowledging leveraging Perplexity, Gemini, ChatGPT, and Claude for research, formatting, testing links, challenging assumptions and aiding the creative process.

LICENSING

Unless otherwise noted, the contents of this series are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Should you choose to exercise any of the 5R permissions granted you under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license, please attribute me in accordance with CC's best practices for attribution.

If you would like to attribute me differently or use my work under different terms, contact me at https://www.linkedin.com/in/marcsramos/.

APPENDICES

Appendix A

Table 1: Anticipated benefits of SBOs based on racial identification [4]

Appendix B

There are many examples where the unsung hero of efficiency gains–tasks–are somewhat unrecognized and uncelebrated. Here is a sampling of research where GenAI’s value in the workplace is fueled and measured at the task-level. Using ChatGPT 4o, we’ve (that is, ChatGPT 4o, Perplexity, and I) mapped the Actual Task(s) being measured in the center column to the Adjacent Skill using O*NET, LightCast, and WEF taxonomy definitions. And there are many.

Table 2: Tasks as AI’s unsung hero and skill enabler

NOTES

Introduction

[1] a real example to better frame this skills versus tasks topic: Erik Brynjolfsson, Danielle Li, Lindsey R. Raymond, (2023), “Generative AI At Work”, http://www.nber.org/papers/w31161 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 April 2023, revised November 2023, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w31161/w31161.pdf

Is the juice worth the squeeze with a Skills-Based Organization approach?

[2] skill building remains a low priority: Sagar Goel and Orsolya Kovács-Ondrejkovic, (2023), “Your Strategy Is Only as Good as Your Skills”, BCG Publications, https://www.bcg.com/publications/2023/your-strategy-is-only-as-good-as-your-skills

[4] shares the same SBO sentiment: “Workplace 2.0: The Promise of the Skills-Based Organization”, (2024), Udemy Business, https://info.udemy.com/rs/273-CKQ-053/images/udemy-business-workplace-2.0-promise-skills-based-organization.pdf?version=0

AI’s unsung, grassroots hero: Tasks

[5] data science capabilities focused on these 3 task areas: Daniel Sack, Lisa Krayer, Emma Wiles, Mohamed Abbadi, Urvi Awasthi, Ryan Kennedy, Cristián Arnolds, and François Candelon, (2024), “GenAI Doesn’t Just Increase Productivity. It Expands Capabilities.”, BCG Publications, https://www.bcg.com/publications/2024/gen-ai-increases-productivity-and-expands-capabilities

[6] notable improvement in the quality of task outputs when leveraging AI tools: Fabrizio Dell'Acqua, Edward McFowland III, Ethan R. Mollick, Hila Lifshitz-Assaf, Katherine Kellogg, Saran Rajendran, Lisa Krayer, François Candelon, Karim R. Lakhani, (2023), “Navigating the Jagged Technological Frontier: Field Experimental Evidence of the Effects of AI on Knowledge Worker Productivity and Quality”, Harvard Business School Technology & Operations Mgt. Unit Working Paper No. 24-013, The Wharton School Research Paper, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4573321#paper-citations-widget

[7] Support agents handled 13.8% more: Erik Brynjolfsson, Danielle Li, Lindsey R. Raymond, (2023), “Generative AI At Work”, http://www.nber.org/papers/w31161 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 April 2023, revised November 2023, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w31161/w31161.pdf

[8] Business professionals wrote 59% more: Jakob Nielsen, (2023), “ChatGPT Lifts Business Professionals’ Productivity and Improves Work Quality”, NN Group, https://www.nngroup.com/articles/chatgpt-productivity/

[9] % increase from Quality and Performance: (2024) “The Impact of Generative AI on Software Developer Performance”, BlueOptima Limited 2005–2024, https://24890502.fs1.hubspotusercontent-eu1.net/hubfs/24890502/The%20Impact%20of%20Generative%20AI%20on%20Software%20Developer%20Performance%20v8.pdf?utm_campaign=The%20Impact%20of%20Gen%20AI%20Report&utm_medium=email&_hsenc=p2ANqtz-9Q_JQi_CHFcHRtz6SpBWOKfQz-PgzWlnqTy1df7vB9xjTsS3GE3R2miq4NzzmwG2ro3cmcqkkgdV3Hn3y2_v5pYNMZWQ&_hsmi=89901551&utm_content=89901551&utm_source=hs_automation

[10] Programmers coded 126% more: Jakob Nielsen, (2023), “ChatGPT Lifts Business Professionals’ Productivity and Improves Work Quality”, NN Group, https://www.nngroup.com/articles/chatgpt-productivity/

[11] work quality improved by 1.3% when using AI: Wiles, Emma and Krayer, Lisa and Abbadi, Mohamed and Awasthi, Urvi and Kennedy, Ryan and Mishkin, Pamela and Sack, Daniel and Candelon, François, (2024), “GenAI as an Exoskeleton: Experimental Evidence on Knowledge Workers Using GenAI on New Skills”, SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4944588 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4944588

[12] business document writing, the average quality rating increased from 3.8 to 4.5: Jakob Nielsen, (2023), “ChatGPT Lifts Business Professionals’ Productivity and Improves Work Quality”, NN Group, https://www.nngroup.com/articles/chatgpt-productivity/

[13] decreased by 0.8 standard deviation: Jakob Nielsen, (2023), “ChatGPT Lifts Business Professionals’ Productivity and Improves Work Quality”, NN Group, https://www.nngroup.com/articles/chatgpt-productivity/

[14] [15] completed 12% more tasks on average… consultants worked 25% faster with 40% higher work: Fabrizio Dell'Acqua, Edward McFowland III, Ethan R. Mollick, Hila Lifshitz-Assaf, Katherine Kellogg, Saran Rajendran, Lisa Krayer, François Candelon, Karim R. Lakhani, (2023), “Navigating the Jagged Technological Frontier: Field Experimental Evidence of the Effects of AI on Knowledge Worker Productivity and Quality”, Harvard Business School Technology & Operations Mgt. Unit Working Paper No. 24-013, The Wharton School Research Paper, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4573321#paper-citations-widget

[16] 90% of participants improved their performance: Jakob Nielsen, (2023), “ChatGPT Lifts Business Professionals’ Productivity and Improves Work Quality”, NN Group, https://www.nngroup.com/articles/chatgpt-productivity/

[17] creative performance increased by 40%: Wiles, Emma and Krayer, Lisa and Abbadi, Mohamed and Awasthi, Urvi and Kennedy, Ryan and Mishkin, Pamela and Sack, Daniel and Candelon, François, (2024), “GenAI as an Exoskeleton: Experimental Evidence on Knowledge Workers Using GenAI on New Skills”, SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4944588 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4944588

[18] burnout appears to be increasing: Upwork Research Institute, (2024), “From Burnout to Balance: AI-Enhanced Work Models”, https://www.upwork.com/research/ai-enhanced-work-models

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES (ALL 7 PARTS OF THIS SERIES)

Wen, J., Zhong, R., Ke, P., Shao, Z., Wang, H., & Huang, M., (2024), “Learning task decomposition to assist humans in competitive programming”, Proceedings of the 2024 Conference of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL 2024), https://arxiv.org/pdf/2406.04604

Wang, Z., Zhao, S., Wang, Y., Huang, H., Shi, J., Xie, S., Wang, Z., Zhang, Y., Li, H., & Yan, J., (2024), “Re-TASK: Revisiting LLM tasks from capability, skill, and knowledge perspectives”, arXiv, https://arxiv.org/abs/2408.06904

Hubauer, T., Lamparter, S., Haase, P., & Herzig, D., (2018), “Use cases of the industrial knowledge graph at Siemens”, Proceedings of the International Workshop on the Semantic Web, CEUR Workshop Proceedings, https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2180/paper-86.pdf

Erik Brynjolfsson, Danielle Li, Lindsey R. Raymond, “Generative AI At Work”, http://www.nber.org/papers/w31161 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 April 2023, revised November 2023, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w31161/w31161.pdf

https://www.royermaddoxherronadvisors.com/blog/2016/april/the-knowledge-worker-in-healthcare/

Connie J.G Gersick, J.Richard Hackman, (1990), “Habitual routines in task-performing groups, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/074959789090047D

Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes”, Volume 47, https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(90)90047-D

World Economic Forum, (2023), “Future of Jobs Report 2023”, World Economic Forum, https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Future_of_Jobs_2023.pdf

Boston Consulting Group, (2024), “How people can create—and destroy—value with generative AI”, BCG, https://www.bcg.com/publications/2023/how-people-create-and-destroy-value-with-gen-ai

Kaisa Savola, (2024), Challenges Preventing Organizations from Adopting a Skills-Based Model”, LinkedIn, https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/challenges-preventing-organizations-from-adopting-savola-she-her--24c6f/

Patel, A., Hofmarcher, M., Leoveanu-Condrei, C., Dinu, M.-C., Callison-Burch, C., & Hochreiter, S., (2024), “Large language models can self-improve at web agent tasks”, arXiv, https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.20309

Sagar Goel and Orsolya Kovács-Ondrejkovic, (2023), “Your Strategy Is Only as Good as Your Skills”, BCG Publications, https://www.bcg.com/publications/2023/your-strategy-is-only-as-good-as-your-skills

“Workplace 2.0: The Promise of the Skills-Based Organization”, (2024), Udemy Business, https://info.udemy.com/rs/273-CKQ-053/images/udemy-business-workplace-2.0-promise-skills-based-organization.pdf?version=0

Shakked Noy and Whitney Zhang (2023): “Experimental Evidence on the Productivity Effects of Generative Artificial Intelligence”, MIT Economics Department working paper. Retrieved March 13, 2023 from https://economics.mit.edu/sites/default/files/inline-files/Noy_Zhang_1_0.pdf

“AI at Work Is Here. Now Comes the Hard Part.”, (2024), 2024 Work Trend Index Annual Report from Microsoft and LinkedIn, https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/worklab/work-trend-index/ai-at-work-is-here-now-comes-the-hard-part

“LinkedIn Workplace Learning Report”, (2024), LinkedIn Learning, https://learning.linkedin.com/content/dam/me/business/en-us/amp/learning-solutions/images/wlr-2024/LinkedIn-Workplace-Learning-Report-2024.pdf

Macnamara BN, Berber I, Çavuşoğlu MC, Krupinski EA, Nallapareddy N, Nelson NE, Smith PJ, Wilson-Delfosse AL, Ray S. “Does using artificial intelligence assistance accelerate skill decay and hinder skill development without performers' awareness?”, Cogn Res Princ Implic. 2024 Jul 12;9(1):46. doi: 10.1186/s41235-024-00572-8. PMID: 38992285; PMCID: PMC11239631, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11239631/

Matt Beane, (2024), “The Skill Code: How to Save Human Ability in an Age of Intelligent Machine”, Harper, https://mitsloan.mit.edu/ideas-made-to-matter/how-can-we-preserve-human-ability-age-machines

Lazaric, N., (2012), “Routinization of Learning”, Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_246

Hering, A., & Rojas, A., (2024), “AI at Work: Why GenAI Is More Likely To Support Workers Than Replace Them.”, Indeed Hiring Lab, https://www.hiringlab.org/2024/09/25/artificial-intelligence-skills-at-work/

Morgan, T. P., (2024), “How GenAI Will Impact Jobs In the Real World”, HPCwire, https://www.hpcwire.com/2024/09/30/how-genai-will-impact-jobs-in-the-real-world/

https://trainingindustry.com/magazine/fall-2022/improving-the-productivity-of-knowledge-workers/

Balasubramanian, R., Kochan, T. A., Levy, F., Manyika, J., & Reeves, M., (2023), “How People Can Create—and Destroy—Value with Generative AI”, Boston Consulting Group, https://www.bcg.com/publications/2023/how-people-create-and-destroy-value-with-gen-ai

Marcin Kapuściński, (2024), “Boosting productivity: Using AI to automate routine business tasks”, TTMS, https://ttms.com/boosting-productivity-using-ai-to-automate-routine-business-tasks/

https://scheibehenne.com/ScheibehenneGreifenederTodd2010.pdf

Paulo Carvalho, (2024), “How Generative AI Will Transform Strategic Foresight”, IF Insight & Foresight, https://www.ifforesight.com/post/how-generative-ai-will-transform-strategic-foresight

Deok-Hwa Kim, Gyeong-Moon Park, Yong-Ho Yoo, Si-Jung Ryu, In-Bae Jeong, Jong-Hwan Kim, (2017), “Realization of task intelligence for service robots in an unstructured environment”, Annual Reviews in Control, Volume 44, ISSN 1367-5788, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arcontrol.2017.09.013.

Kweilin Ellingrud, Saurabh Sanghvi, Gurneet Singh Dandona, Anu Madgavkar, Michael Chui, Olivia White, Paige Hasebe, (2023), “Generative AI and the future of work in America”, McKinsey Global Institute, https://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/our-research/generative-ai-and-the-future-of-work-in-america#/

MIT Technology Review Insights, (2024), “Multimodal: AI’s new frontier”, https://wp.technologyreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Jina-AI-e-Brief-v4.pdf?utm_source=report_page&utm_medium=all_platforms&utm_campaign=insights_ebrief&utm_term=05.02.24&utm_content=insights.report

Sandra Ohly, Anja S. Göritz, Antje Schmitt, (2017), “The power of routinized task behavior for energy at work”, Journal of Vocational Behavior, Volume 103, Part B, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.08.008

Baddeley, A.D. (2003). Working memory: looking back and looking forward. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 4, p.829-839, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14523382/

Baddeley, A.D. and Hitch, G. (1974). Working Memory. Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 8, p.47-89, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982209021332

Chandler, P. and Sweller, J. (1991). Cognitive Load Theory and the Format of Instruction. Cognition and Instruction, 8 (4), p. 293-332, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1207/s1532690xci0804_2

Chandler, P. and Sweller, J. (1992). The split-attention effect as a factor in the design of instruction. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 62 (2), p.233–246, https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1992.tb01017.x

Clark, R.C., Nguyen, F. and Sweller, J. (2006). Efficiency in learning: evidence-based guidelines to manage cognitive load. San Francisco: Pfeiffer, https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1992.tb01017.x

Marzano, R.J., Gaddy, B.B. and Dean, C. (2000). What works in classroom instruction. Aurora, CO: Mid-continent Research for Education and Learning, https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1992.tb01017.x

Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive Load during Problem Solving: Effects on Learning. Cognitive Science, 12, p.257-285, https://mrbartonmaths.com/resourcesnew/8.%20Research/Explicit%20Instruction/Cognitive%20Load%20during%20problem%20solving.pdf

Wenger, S.K., Thompson, P. and Bartling, C.A. (1980). Recall facilitates subsequent recognition. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory, 6 (2), p.135-144, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00012.x?journalCode=ppsa

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00012.x?journalCode=ppsa

Choi, S., Yuen, H. M., Annan, R., Monroy-Valle, M., Pickup, T., Aduku, N. E. L. & Ashworth, A. (2020). Improved care and survival in severe malnutrition through eLearning. Archives of disease in childhood, 105(1), 32-39. Doi:10.1136, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31362946/

Chyung, Y. C. (2007). Learning object-based e-learning: content design, methods, and tools. Learning Solutions e-Magazine, August 27, 2007, 1-9. https://www.elearningguild.com/pdf/2/082707des-temp.pdf.

https://dobusyright.com/druckers-six-ideas-about-knowledge-work-environments-dbr-031/

Doolani, S., Owens, L., Wessels, C. & Makedon, F. (2020). vis: An immersive virtual storytelling system for vocational training. Applied Sciences, 10(22), 8143, https://ouci.dntb.gov.ua/en/works/l1mwRvyl/

Gavarkovs, A. G., Blunt, W. & Petrella, R. J. (2019). A protocol for designing online training to support the implementation of community-based interventions. Evaluation and Program Planning, 72(2019), 77-87, https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2018-61336-010

Kraiger, K. & Ford, J. K. (2021). The science of workplace instruction: Learning and development applied to work. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 8, 45-72.

Longo, L. & Rajendran, M. (2021, November). A Novel Parabolic Model of Instructional Efficiency Grounded on Ideal Mental Workload and Performance. International Symposium on Human Mental Workload: Models and Applications (pp. 11-36). Springer, Cham, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/354893819_A_novel_parabolic_model_of_instructional_efficiency_grounded_on_ideal_mental_workload_and_performance

Merrill, M. D. (2018). Using the first principles of instruction to make instruction effective, efficient, and engaging. Foundations of learning and instructional design technology. BYU Open Textbook Network. https://open.byu.edu/lidtfoundations/using_the_first_principles_of_instruction

Rea, E. A. (2021). "Changing the Face of Technology": Storytelling as Intersectional Feminist Practice in Coding Organizations. Technical Communication, 68(4), 26-39, https://g.co/kgs/XAhhL77

Schalk, L., Schumacher, R., Barth, A. & Stern, E. (2018). When problem-solving followed by instruction is superior to the traditional tell-and-practice sequence. Journal of educational psychology, 110(4), 596, https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2017-57179-001

Shipley, S. L., Stephen, J. S. & Tawfik, A. A. (2018). Revisiting the Historical Roots of Task Analysis in Instructional Design. TechTrends, 62(4), 319-320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-018-0303-8

Smith, P. L. & Ragan, T. J. (2004). Instructional design 3rd Ed. John Wiley & Sons, https://www.amazon.com/Instructional-Design-Patricia-L-Smith/dp/0471393533

Willert, N. (2021). A Systematic Literature Review of Gameful Feedback in Computer Science Education. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 11(10), 464- 470, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/354317969_A_Systematic_Literature_Review_of_Gameful_Feedback_in_Computer_Science_Education